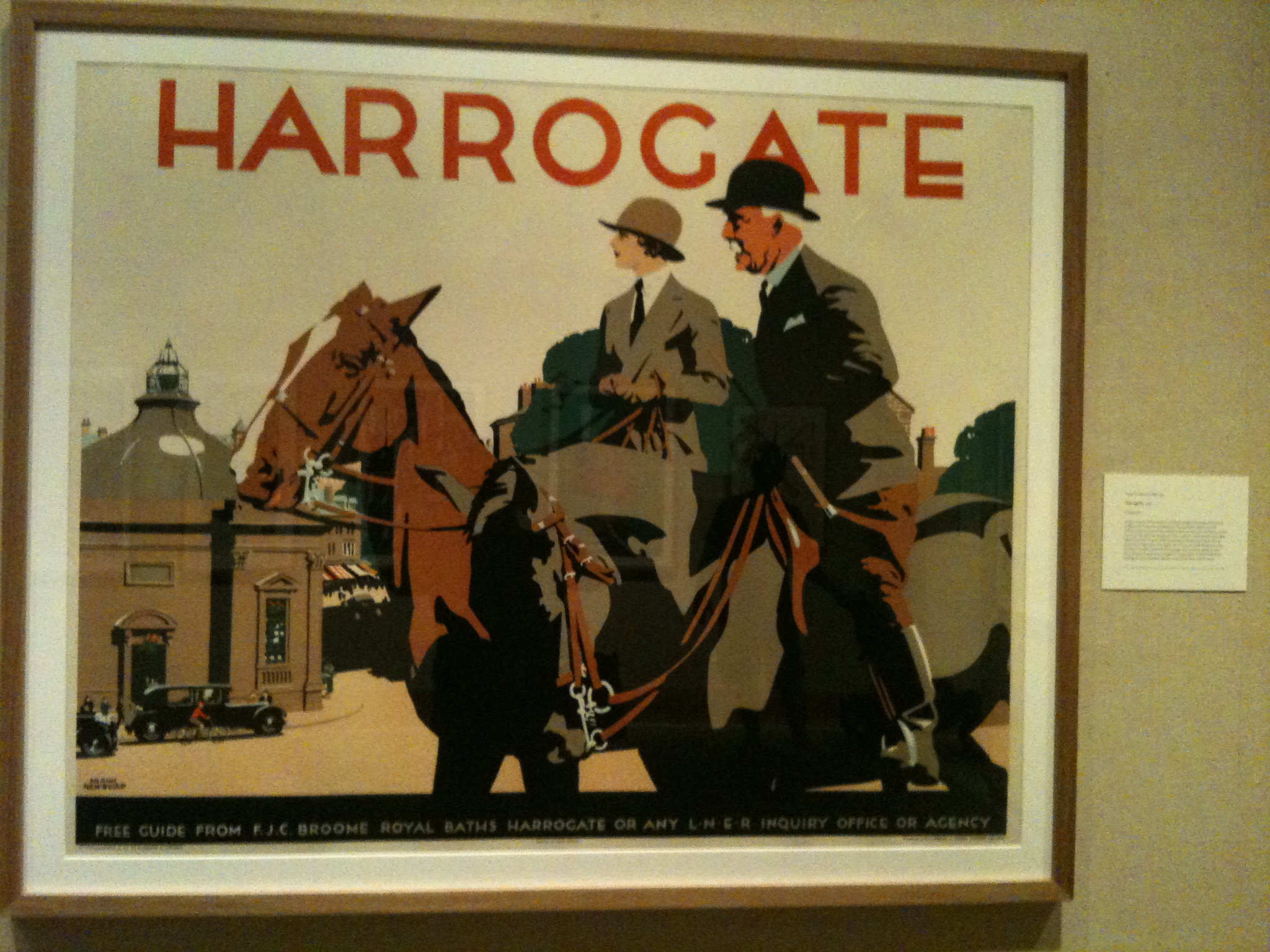

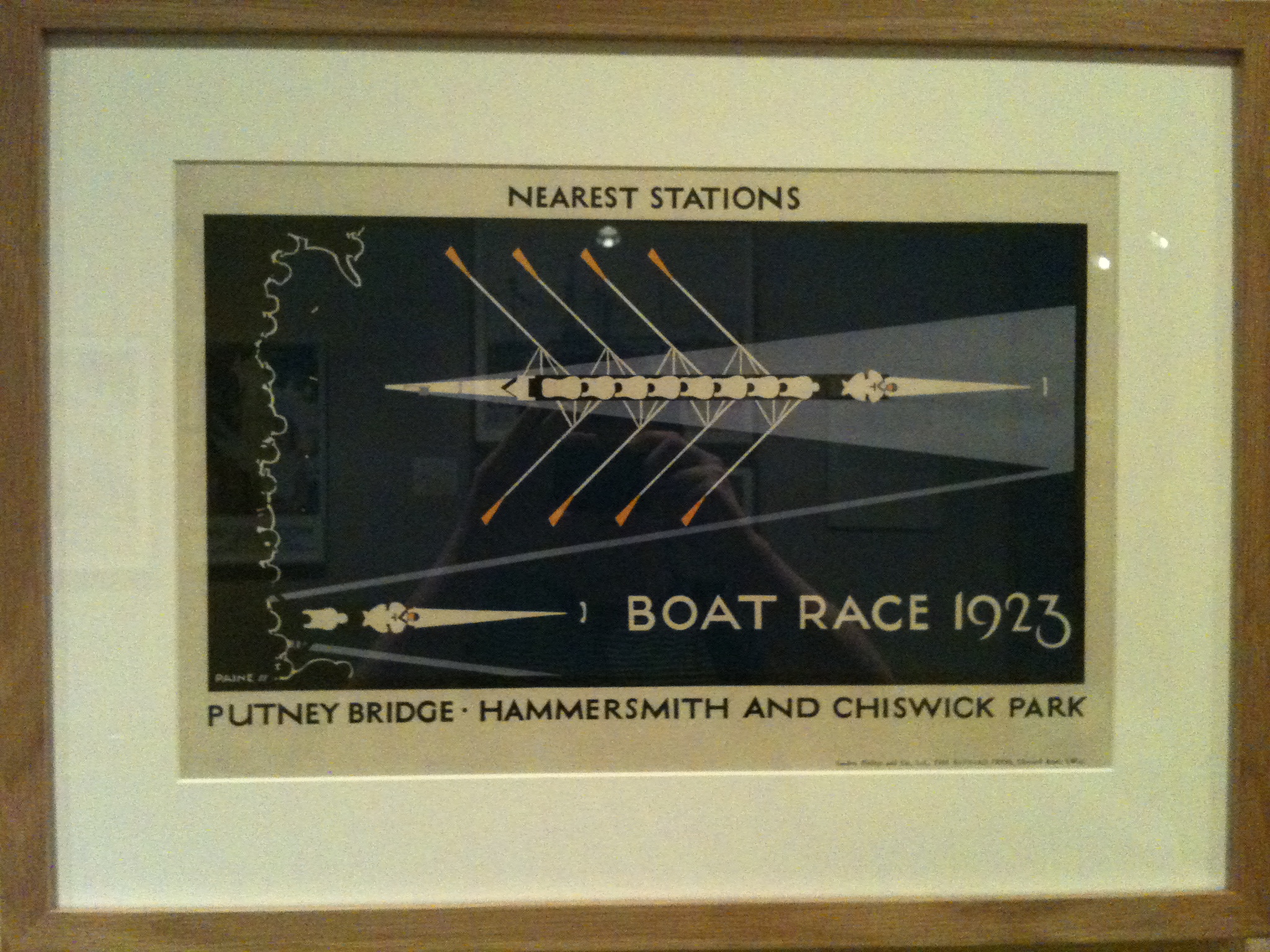

The afternoon was spent perusing the various art museums here on Yale’s campus. In one there was the standard fare: the oil paintings of Jesus and nobles and the poor at work, the amorphous sculptures characteristic of the middle of the twentieth century, and many other categories not named here. From each, the quintessence of the genre, its cream of the crop, so to speak, was on display. But at the museum of British art, there was an exhibition of posters from the various railed transportation systems of London (i.e. the Underground) and the various train lines that conveyed haggard city-dwellers to the country and the coast.

On display were popularized conceptions of the idyllic life, one that, for the Brits, can be reduced efficiently to platitude:

It is, of course, more than this, more than platitude, than distilled zeitgeist, than a superficial “takeaway” from the work. For better or worse, it is a charming way to look at things, to romanticize and to gloss over a thing’s faults. I suppose I, to a certain degree, am guilty of this in my WASPy Ivy League romanticization of my experience visiting Yale. Romanticism implodes when it is “found out” to be a farce, a facade–that the quality celebrated in something turned out to be non-existent: the very product of the smoke and mirrors of romanticism.

There is, however, much to love about the old buildings of New Haven, the students studying here, the strange feeling of superiority (of questionable merit, but nonetheless omnipresent), and–it must be said–the deeply evocative, fundamentally romantic, statement made by the students after they leave here for the autumn, that they, if only for a summer, were a part of the “Ivy League.” In so, the romantic notions of the Ivy League are substantiated, and are thus not the product of romanticism but the product of a certain quality conferred upon those who come here. I asked a friend about what one might call this quality. “I don’t know, man. How one would qualify it as something objective? You know, binary, something that one either possesses or lacks. Sounds like romanticism to me.”

Leave a Reply